Text from my duty on December 13, 1981 at the MKZ NSZZ "Solidarność"

in Yaroslavl, and from Christmas Eve at the "internment center," i.e. the prison in Uherce.

MY TWO NIGHTS IN DECEMBER

December 13, 1981

That evening in the building of the Inter-company Trade Union Commission

The NSZZ "Solidarity" in Kraszewskiego Street in Yaroslavl was put on duty by a group of trade unionists from the San Confectionery Factory: Franciszek Łuc, chairman of the company committee of the NSZZ "S", Julian Mizgiel, an employee of the mechanical workshop at the San

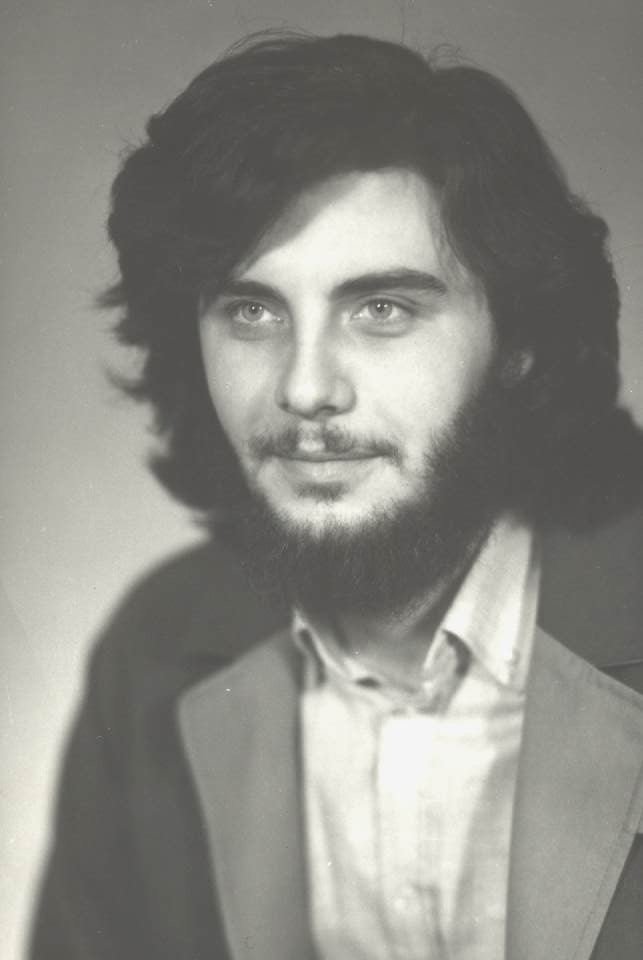

and Andrzej Wyczawski, an employee of the quality control and laboratory of the San and the Information Section of the MKZ NSZZ "S" in Jaroslaw.

A strike alert was in progress, and white and red flags hung on some houses. Although there was talk of a state of emergency, and two days earlier I received a poster from the Mazovia Region, on which a tank is crushing with its tracks a bundle of writings signed: August Agreements, and above it all the inscription: STATE OF WAR - duty began peacefully.

The first alarming sign was information about the movements of large columns of the army. The phone rings - an acquaintance notifies Frank "... to know (that he saw moving columns of the army, which was not an ordinary event)...". Anxiety grows.

I call MKZ chairman Kazimierz Ziobra. He doesn't believe it, he thinks it's a prank on my part. (Kazimierz was later on strike against martial law at the Jaroslaw Glassworks and, disguised as a priest, was led out of the Glassworks by Solidarity people.)

However, after other signals, he arrives with Ryszard Bugryn, Tadeusz Slowik, Zygmunt Woloszyn. After a brief discussion, Kazik (Ziobro) states that it is necessary to look around the city and leaves with his colleagues.

In the meantime, we connect by telex with the region in Przemyśl - they already know about the situation, we set the password "KOR" for the next connection, should there be an attack by the militia or ZOMO.

Franek leaves the MKZ, goes to the post office and returns immediately, seeing a soldier in a helmet with a gun standing in front of him. Mr. Roman Zeman and Mr. Waclaw Zeman come in

From Solidarity Health Care - again a short conversation. They leave. We are left alone. Time passes. It's about 11:30 pm on the telex "caller" a light comes on, which means it has been turned off!!!

Franek Luc calls the Telecommunications Office in Yaroslavl and asks what happened.

The voice in the headset replies that it has been turned off on command. The pressure is rising, we already know that something thick is being prepared, but we don't yet suppose that they might come after us. Shortly before midnight, the phone also goes silent. We are cut off from the world. I turn on the radio, they are just now broadcasting a daily newspaper on program I, the announcer mumbles something about strike alert and extremism

From Solidarity.

Julek Mizgiel looks out the window. "They're coming," he says. "Who?" - asks Franek. "Not the fire department, after all," replies Julek. I run up to the window. Along the fence a goose-stepping, stealthy movement of at least a dozen ZOMO men with ... peems. There is no time to count them. Under the blows of their butts, with the clink of broken glass, the first glass front door in Dr. Zasowski's former pre-war villa falls out....

At the moment when I run to the "connecting passage" between the MKZ building and the ART-club "Jarlan" and stop in front of the door closed on the other side, Franek Luc tries to jump out of the toilet window, but quickly gives up to avoid jumping on the back of a standing militiaman. Back in. Downstairs, the attackers are banging their butts against the other solid oak door, trying to get inside, but this solid pre-war door doesn't think to give way.

After a short deliberation, following desperate logic so as not to prolong the tension, I go downstairs with Julk Mizgiel and we open the door. Then with a shriek: "Enough of this!", "it's over!" an SB-ek rushes in, followed by another one and a large group of ZOMO-wielders with peems and "Kalach" guns pointed at us. The SB-ek - as it later turned out the commander-in-chief of the whole "action" - without slowing down, runs up the stairs to get Frank. I see that the ZOMO-wielding young boys, like me, are very frightened, which does not comfort me at all, because I feel that it will be easier for them to pull the trigger in this state. I put my hands up, lean my back against the wall and prefer to avoid with my eyes the barrel of the peem, which is stuck near my head....

We were quickly searched, ordered to take off our shoes, which were also thoroughly checked. Later there was a search combined with the confiscation of all the documentation of the Solidarity Trade Union's MKZ, money, telex, and even the head from the banner, because on it the eagle had a crown. The SB's commander-in-chief, supposedly the head of the department, hollered: "What is this!!!

What the fuck is that!!!" - as if it were some kind of crime that the eagle has a crown! And it was significant, thanks to the confusion he himself had caused, that he forgot about the banner of the MKZ NSZZ "S", which, in the morning after a daring action, was carried out of the MKZ, earlier observing the secret police, by Pawel Niemkiewicz, a Jaroslaw poet and his spokesman at the time. The banner, beautifully embroidered by the nuns (today I do not remember what congregation they were from) thanks to him survived martial law and more!

I remember how, after internment, the same esbek summoned me for interrogation in Przemyśl

and threatened that if I told people what it was like during the internment and if I said what he said during my interrogation, they would find me and do "whatever it takes." It is worth adding that I was summoned to the SB in Przemyśl in the "capacity of a party," that is, unlawfully, because then you could be summoned as a witness or suspect.

Also taken away was the entire library of "independent publications," organized mainly by myself and Malgorzata Osada-Gajewicz. Into the militia bags were thrown, among others, editions of Czeslaw Milosz, Kazimierz Wierzynski, Witold Gombrowicz, Kazimierz Brandys, George Orwell (and, among others, my then-favorite "A Little Apocalypse" by Tadeusz Konwicki, which I had previously only been able to listen to on Radio Free Europe); mostly published in the second circuit, of course, outside the censorship by the Independent Publishing Office NOWA!

At the same time, another group (three in civilian clothes, three in uniform), looking for me, was forcing the door of my parents' apartment. My father refused to let them in and open the door to the apartment. Rifle butts and a crowbar were in motion. The door was broken down (to this day there is a mark on it from that event). A neighbor trying to intervene, Mr. Edward Wawrzyniak, was hit with all his might and violently pushed back into his apartment.

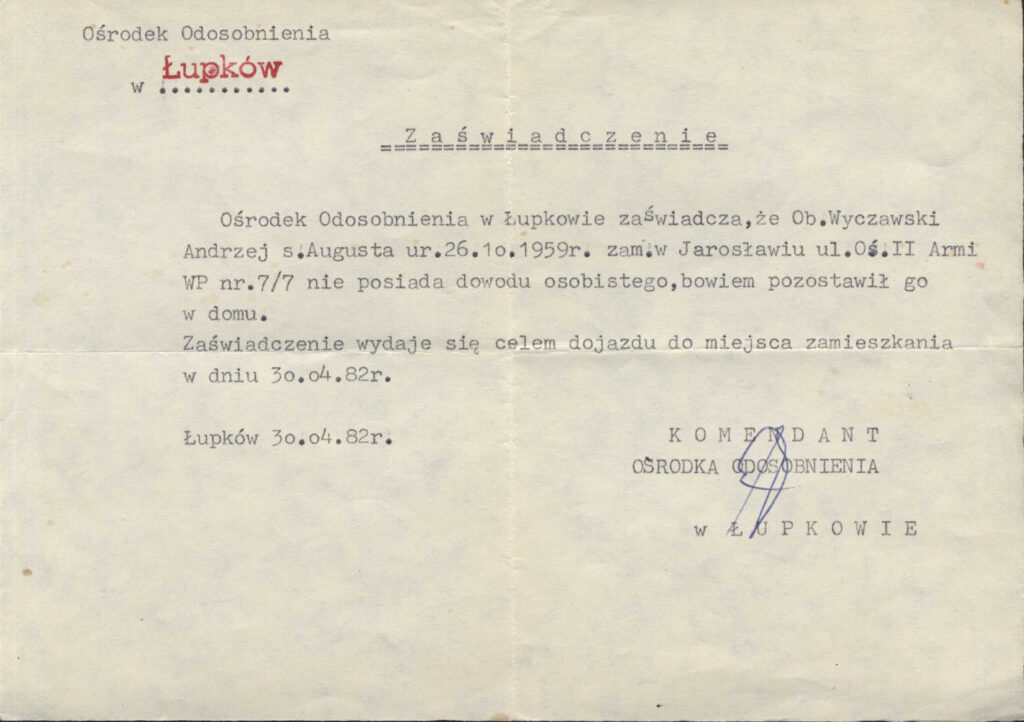

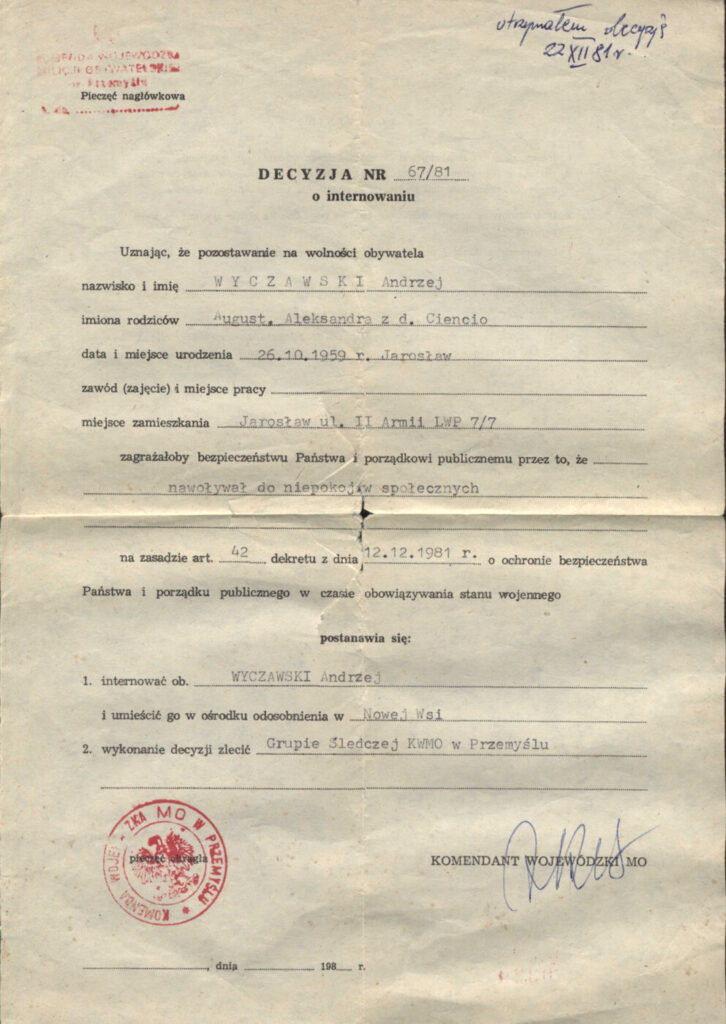

From the MKZ NSZZ "Solidarity" in Kraszewskiego Street, we were taken to the MO headquarters in Yaroslavl, and were led into separate rooms on the second floor. The "act of internment" included the inscription: "Incited to social unrest", "Place of isolation - Nowa Wieś (Uherce).

In the morning, I was pushed into a police gauze car, where Mr. Mieczyslaw Kolakowski, head of Solidarity, was already sitting handcuffed by the arm to the armchair railing

At the Telecommunications Office in Yaroslavl. I was also chained in the same way next to him.

A convoy of more than a dozen militia bitches and gassers set off in the direction of Przemyśl. On a cold December morning, people were walking to church. I heard Jaruzelski's memorable speech on the car radio. Thus began the first day of the war against the Nation.

December 24, 1981, Christmas Eve

Cell No. 22, closed from the outside, in the prison block of the Uherce prison headquarters,

(Uherce was then called - Nowa Wieś - in accordance with the Gierek nomenclature for removing place names of Ukrainian origin). "Kurevska", as the keyboardists say. An area of about five meters by two and a half. Eight beds, four piled on each wall, a table, two stools, a hanging cupboard and a loo in the corner, in plain sight.

There are seven of us: Mr. Jan Połoch and Jurek Czekalski from Lubaczow, Bogdan Dąbrowski a railroader from Jaroslaw, working at the railroad station in Zurawica, Andrzej Szewczyk from the Glassworks in Jaroslaw, who later emigrated to the USA, Mieczyslaw Kolakowski and myself from Jaroslaw, and farmer Mietek Ważny from Oleszyce. Outside the barred window a dull frost - it was reportedly below twenty-four degrees C - in the cell twelve degrees. I sleep on the bunk "downstairs," wearing a sweater, scarf and gloves (I got sick anyway, and Dr. Cichulski from Przeworsk, after consulting with Dr. Gąska, a well-known and respected laryngologist from Przemyśl, treated me with smuggled medicines that he had obtained only by his known means).

The block we are in is located at the top of a hill, so it blows mercilessly - we try to seal the windows with whatever we can. We are all after a seven-day protest hunger strike against the application of the rules and regulations for temporary detainees to us. Among other things, it ordered us to report at the prison roll call every morning the condition of the prisoners, saying to the higher-ranking warden "citizen educator," and finally to put our clothes, previously arranged in a so-called "cube," in front of the cell.

We take out the prison aluminum bowls and spoons, and prepare the table for Christmas Eve. The first from our cell got a package Mr. Mieczyslaw Kolakowski, in the afternoon my parents arrived

and Jurek Czekalski's brother. At the so-called visitation in the prison administration room, under the watchful eye and ear of the keymen, who are always ready to interrupt the visitation on any pretext, the first meeting with the parents. I sit all the time wearing a jacket and gloves. Parents are surprised that I don't take them off. I say that I'm cold, that in bed I sleep in a sweater, wrapped in a scarf and wearing pants. I can see that they don't believe it. They only breathed a sigh of relief when I took off my gloves (because they thought they were beating me).

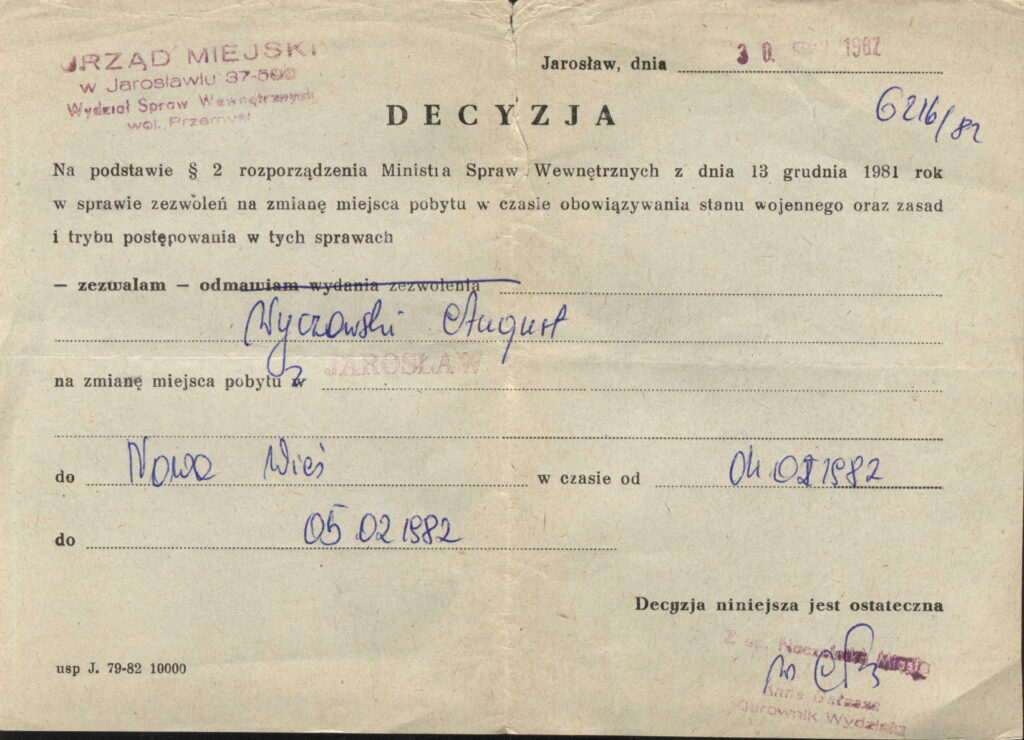

They drove here almost half a day from Yaroslavl by private transport, two hours they stood in the cold in front of the gate (as they told me), according to the head of the prison - to "repent", they would return home maybe after ten in the evening.

In the cell, we share the supplied wafer, food, sing carols, listen to the broadcast of the shepherdess from the prison "kolkhoz" and the homily of Primate Glemp, carrying words of condemnation to Herod for the slaughter of innocent children. This is how the wartime Christmas Eve passes.

PS

All of them (my interned colleagues at the time), whom I later asked about their memories of that wartime Christmas Eve, confirm that not much of the sadness remained in their memories, as if they wanted to remember the nascent God at the time as a ray of hope.

.

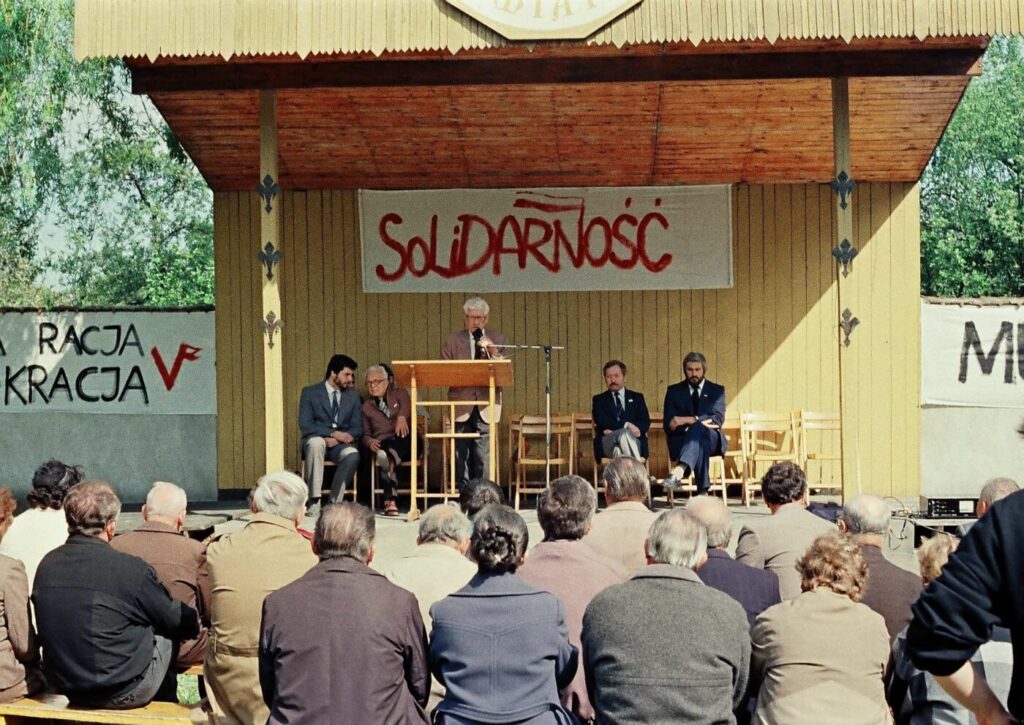

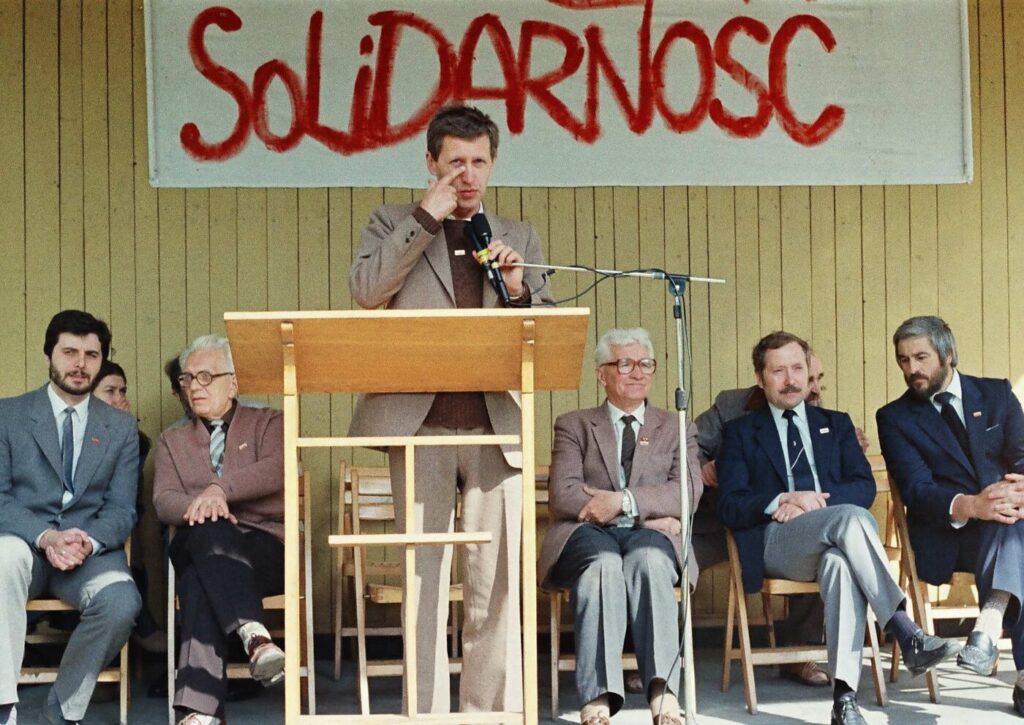

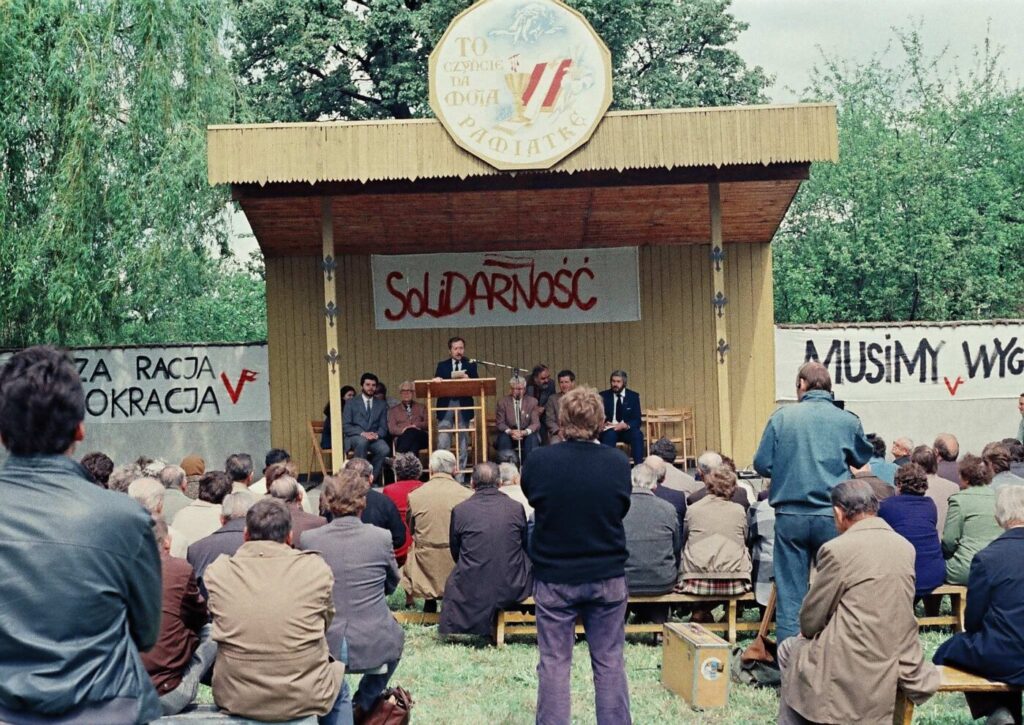

On June 4, 1989, partially free parliamentary elections were held under agreements between the communist authorities and part of the opposition. Solidarity's victory opened a new era in Poland's recent history and influenced the process of the collapse of communism in Central Europe.

In Jaroslaw in mid-1988, the Inter-Union Trade Union Commission of the Solidarity Trade Union was already thriving, bringing together trade union representatives of all the largest and most important workplaces. At that time, on the recommendation of Tadeusz Ulma during the elections to the MKZ, I became its chairman.

The main goal, as everywhere in Poland at the time, was the re-legalization of the NSZZ "Solidarity"

and the expansion of its structures and the change of the political system in Poland.

The "Solidarity" Civic Committee in Jaroslaw at the time consisted of: Bronislaw Niemkiewicz - chairman, Andrzej Wyczawski - deputy chairman, Jaroslaw Pagacz - secretary, as well as Wladyslaw Kordas, Pawel Niemkiewicz, Ryszard Bugryn, Bogdan Dabrowski, Waclaw Zeman, Roman Zeman, among others.

The elections were held under the slogans "Elected for you, now choose for yourself," "Vote for the Solidarity opposition," and "Our right - democracy."

Candidates of the Solidarity Civic Committee were elected to the Sejm and Senate: Tadeusz Trelka and Janusz Onyszkiewicz to the Senate Tadeusz Ulma and Jan Musial. It was a big win, as was the case throughout Poland.

They were followed by elections ordered for the day by Prime Minister Tadeusz Mazowiecki on May 27 in 1990. These were the first elections to local self-government in Poland after its restoration (it was abolished in 1950 and replaced by national councils for four decades), and it was one of the most important changes to the democratic political system in Poland.

In Yaroslavl, 26 out of 32 seats on the Yaroslavl City Council were just won by candidates of the Solidarity Civic Committee. As a result of the election, I become a councilman and a member of the Jaroslaw City Council, which positions I will hold for 3 terms from 1990 to 2002.

On the other hand, in 2002-2006, I become an alderman of the Jaroslaw district and a member of the board of the Jaroslaw district. In 2006, after another local election, I become the mayor of Jaroslaw, and I will hold this position for 2 terms - from 2006 to 2014.

At this time, new political parties are being formed, taking over political activities from the Civic Committees. The first party active in the former Przemyśl province is Porozumienie Centrum, which I join thanks to Marek Kuchcinski, founder of the PC in Podkarpacie. At the time, Porozumienie Centrum demanded a break with the previous policy of Tadeusz Mazowiecki's government, which was accused of, among other things, moving too slowly away from the past and the remnants of the People's Republic of Poland. The new perception of the duties and tasks that local self-government has within its competence, i.e. the realization of the needs of the residents, democratic cooperation with local associations and other non-governmental organizations of the residents was characterized primarily by the creation of local "small homelands", which primarily dealt with catching up with the backwardness and many pressing problems of the residents, usually impossible

to be implemented in the former Pezetpeer regime. They gave an impetus to residents to become creatively personally involved in the affairs of local municipalities and their issues related to neighborhoods, streets, schools or local infrastructure. This was a true victory for democracy and the final undoing of the communist past.

.