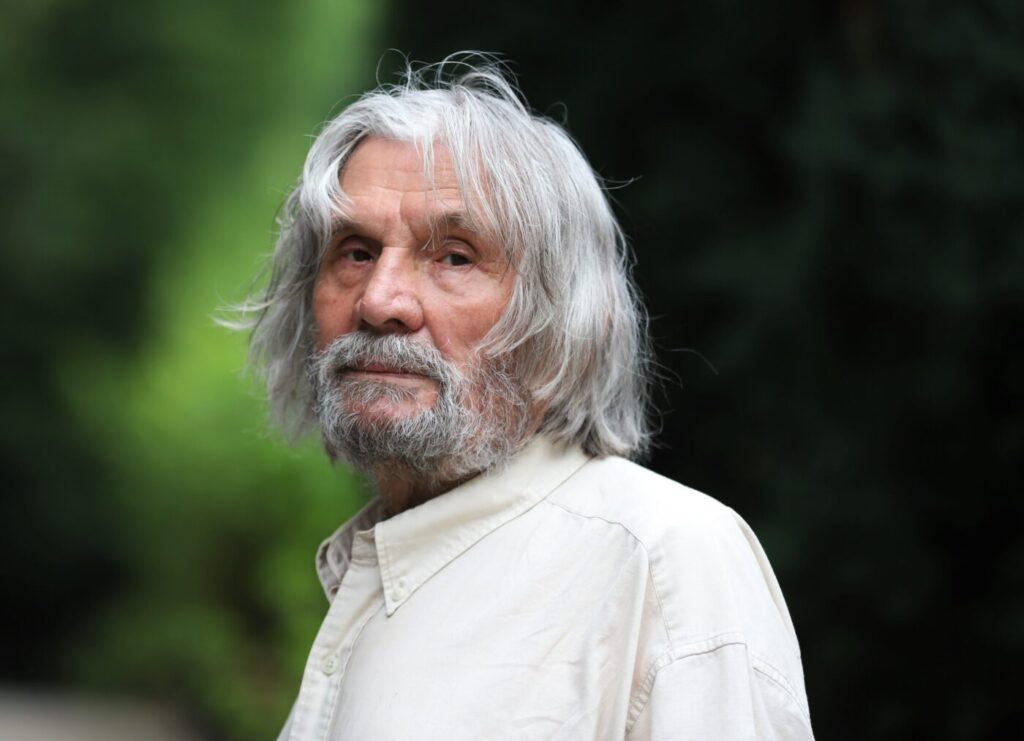

Professor Jerzy Piórecki

When we look at the Arboretum, it is hard to imagine the immense amount of time and work required to create this wonder of nature. However, it is not the work of nature and human hands alone. The professor's vast knowledge helped. And then there's the heart. The plants feel it. As we walk, Jerzy Piórecki names the plants one by one, most of which I see for the first time in my life. The place is famous for its dogwood, of which there are more than three thousand varieties here. There are also exotic plants, and I wonder how they, brought somewhere from American wetlands or another Amazon basin, are accepted in Podkarpacie, have lived for so many years and are growing beautifully. Perhaps the professor has possessed secret knowledge that he will share with me someday.

We live in a reality determined by the war in Ukraine. Poles have changed the paradigm of helping refugees, which has affected the positive perception of us in the world and given us a greater right to claim "our own." In recent days, there has been a lot of buzz about the unveiling of lion statues in front of the cemetery of Lviv's Eaglets. I know from Mariusz Olbromski that he and Professor Piórecki did quite a "guerrilla warfare" so that our fallen compatriots would rest in a dignified place - no trash, no debris, in the shelter of nature. So I am glad to have the opportunity to ask about this remarkable story in person.

Jerzy Piórecki:

We transported plants to Ukraine in an extremely difficult way. The worst was the transportation, as there were no similar solutions that carriers have today - with documents at the border we stood for several hours at a time. To give seriousness to the matter, we collected all possible stamps - for example, with St. Florian, it was then considered an important institution. The more stamps one earned, the easier it was to cross the border. Queues at the border were several kilometers each. People in large clusters camped for days in the ditches and greenbelts that exposed the roadside. When Mariusz and I rode in a privileged consular car, people who were nervous, tired, with children jumped on the hood of the car to stop us from bypassing the crowded travelers.

Whose initiative was it?

It should not be forgotten that at that time in many localities in Poland spontaneous initiatives arose - how to save in the then reality of Polish heritage in the lost lands. I found myself in the group of initiatives on how to carry out cleaning and maintenance of the woody greenery in the Lychakiv cemetery.

The initiative did not cross Poland's borders due to a lack of adequate equipment and people with adequate training.

However, Przemyśl is the closest to Lviv, and seemingly as a shortcut, according to Mariusz Olbromski - as an accompanying person I found myself with him at talks with the authorities of the city and Lviv region. The course of them was recounted by Mariusz Olbromski. For my part, I would like to add that at the recent stormy meeting at the Lviv City Hall, he caused, among other things, an interpreter, adding a number of additional claims to the speeches of the participants of the meeting, on the issue of giving the Ukrainians architectural objects in Przemyśl as a basis for the talks.

Today it can be said that the Ukrainian side recovered much more of them, with the exception of the church and monastery of the Carmelite Fathers of Martin Krasicki's foundation. In the following long years, the authorities of the Republic gradually, at the expense of Przemyśl, with great pauses and slowly obtained permission from the authorities of the city of Lviv for the restoration of the military cemetery in Lychakiv Cemetery.

At the meeting in Lviv, Mariusz Olbromski, equipped with a letter of intent on behalf of Przemysl Voivode Jan Musial, declared cooperation between the Przemysl Voivodeship and the Lviv Regional National Council, expressing care for Ukrainian cemeteries in the Przemysl Voivodeship, and on the Ukrainian side offering to take care of Polish cemeteries in the Lviv region.

Talks about salvage work at military cemeteries became impossible to continue, and anything else could not be discussed at all.

There, in the catacombs, there was still a railroad locomotive that heated the stonemason's workshop in winter. Many of the stonemason's materials came from the Triumphal Arch of the Cemetery of the Eagles or other Polish monuments. The upper part of the military cemetery with the chapel and catacombs was separated by a wall of concrete blocks from the cemetery (Fig. 5), which did not actually exist, as the ground was platted and leveled with rubble, garbage and soil from the nearby excavations of newly erected buildings. The height of the embankment ranged from two to four meters or more. Crosses from gravestones were brought in as sleepers for a nearby streetcar line.

One of the most interesting moments of the meeting was the quiet requests of Tadeusz Bobrowski, director of Energopol, a large company doing construction work on fertile soils near Lviv at the time. As I mentioned, the director repeatedly asked for permission so that the company could bring soil to the cemetery for the restoration of gravestones with its own transport, while also asking for written permission for the company to enter the cemetery. In view of the official refusal to receive written permission, the deputy chairman of the Lviv Regional National Council, who was leading the meeting, said that no special letter was needed, since the director of Lychakiv Cemetery was present in the room, and why not communicate. It was as if it was a discreet agreement between the two gentlemen, i.e., Director Bobrovsky and Director of Lychakivsky Cemetery, that they would handle the matter, which in fact turned out to be real, and the Energopol company not only brought a heap of fresh soil, but first of all, with its own transport, began removing heaps of rubble and soil from the cemetery. Previously, by hand, mainly people from the Society for the Care of Military Graves in Lviv collected rubble and soil from the gravestones and carried them away in various containers and wheelbarrows to the heaps, and decorated the free space between the gravestones with plants (Fig. 1).

In the first phase of caring for the exposed graves, the women of the Society spontaneously planted ornamental plant species that grew near their home, i.e. ornamental plants - ground plants - annuals, which required care (Fig. 4). As winter came, they died, and had to be planted anew in the spring.

The work was directed primarily by Eugeniusz Cydzik (Fig. 6). From then on, an energetic group of people from Energopol spontaneously and with the help of director Tadeusz Bobrowski undertook the long-standing effort to clean up the military cemetery during off hours. Deconstruction revealed intact tombstones, but already without crosses. The biggest problem was the removal of the large poplar trees from the avenue laid out on the main axis of the cemetery - between the Triumphal Arch and the chapel, but this too was handled by Energopol employees and the director.

After the unveiling of the plots already at the new plantings, we had various adventures transporting plants from Poland to Ukraine. On one of the trips, together with a colleague Tomasz Nowak, director of the Botanical Garden of Wrocław University, who collected plants for planting and at the same time turned out to be an important specialist in packing them into cars. He was able to stuff an infinite number of pots into a nysa. We pulled up at the border in Medyka, at the time it was the fashion in Ukraine to transport potato tubers from Poland. The plant quarantine specialist became interested in the stamps from the botanical garden, and if it weren't for that, she would probably still think we were carrying potatoes and give us permission to transport them. We, however, confirmed it, and consultations with Kiev began anew. Not even Mr. Tomasz's fervent assurances that we were carrying a gift for the Ukrainian people and the city of Lviv helped. After many hours, we were informed that there was a buffet for border guards on site, and we struggled to get through the long hours of waiting for permission to leave. We succeeded mainly because a colleague put his shoe between the doors to the buffet and would not let them close. We spent many hours there, on the shelves of the buffet there was pork fat red from peppers and a large cauldron of sweet coffee generally available. At these we spent almost eight hours at the buffet, until the final information was made available to us that our Nysa car was unprepared for transport. At the end of the day, we meet with the plant quarantine worker one more time and, at her request, open the back door of the Nysa, from which dozens of plant pots spilled out at us. The lady from the office takes one of the first pots and removes a juniper sapling from it, and half a pot of earthworms falls out onto it. After a couple of hours we managed to cross the border. From then on, the transport of plants from Bolestraszyce to Lviv was taken on by Energopol.

And for many years we planted junipers on each new exposed grave. First fast-growing, and then with slowed growth very low, not requiring frequent pruning. Over a period of time, companies associated with the restoration of the cemetery replaced the juniper plantings with stone gravel, which also became overgrown with weeds, and after some time, through the efforts of Tadeusz Cydzik and others from the Society for the Care of Military Graves, the form of juniper plantings became established (Fig. 2-5).

Interviewed by Marta Olejnik

The long-time and persistent caretakers of the Cemetery of the Eaglets from the Society for the Care of Military Graves in Lviv were the first to uncover tombstones from under the rubble and care for the flowers on them. Visitors to the Arboretum in Bolestraszyce in 1994 visited Przemyśl, Calvary Paclawska and Czestochowa

During the period of their stay at the Arboretum, the guests from Lviv, under the care and vivisection of Father Henryk Pszony, visited Krakow, Lagiewniki, Czestochowa and Kalwaria Paclawska. They were accompanied from the Arboretum by Marzena Kluz and Kazimierz Kozak. Transportation was lent by the director of PKS from Przemyśl

Mariusz Olbromski

Of course, I confirm what Professor Jerzy Piórecki said. I would only add that he raised, among other things, a matter completely unknown to the public. Well, at the beginning of the 1990s, as director of the Department of Culture, Sports and Tourism in the Przemyśl Provincial Office, I conceived and wrote a project to sign an agreement between the then Przemysl and Lviv provinces on the mutual protection of cemeteries. I was mainly concerned with the Lychakiv Cemetery of the Eaglets, but not only. Because I have, for example, my relatives buried in the cemetery in Yavoriv. And at that time these border cemeteries looked terrible, everything was destroyed and littered. So I persuaded the then governor of Przemysl, Jan Musial, to send me to Lviv with this project, which was also translated into Ukrainian, and authorize me to hold talks on the matter. And before that, he notified the authorities in Warsaw. I was accompanied on the trip by Prof. Jerzy Piórecki, who traveled, among other things, to see what the Cemetery of the Eaglets looked like. Being older and more experienced, he offered me his advice. At the Lviv City Hall, I held talks with the Ukrainian side (there were about forty people), but Prof. Jerzy Piórecki was also present, as well as other people in whom I had confidence: the late Stanislaw Czerkas, president of the Polish Cultural Society in Lviv, the late Emilia Chmielowa, president of the Federation of Polish Organizations in Ukraine. All of these people joined the conversation and provided me with support. Also the Polish consul in Lviv, whose name, unfortunately, I do not remember. Also present at the meeting was Mr. Tadeusz Bobrowski, director of Energopol, a large Polish company that had a base near Lviv and had several hundred trucks at its disposal. It employed several hundred workers. After more than three hours of talks at the Lviv City Hall, I had a sense of defeat, because the Ukrainian side ultimately refused to sign the document. So I asked the chairman of the city council at the end, before saying goodbye, if it would be pleasant for him to have garbage lying on the graves of his loved ones, and he seemed to suddenly come to his senses and replied that it would not. "Then let you and your colleagues think about how the families of those people who lie in the Orląt cemetery feel," I said. "Agree to at least take out the garbage." To which he - after talking to councilors and advisors - agreed, but did not sign anything. He only said that they would open the gates of this cemetery, but only for a month and no longer. I walked out of the City Hall hall hall with a sense of defeat, but Director Bobrowski came up to me and said: "Ladies, this is a great success. This is the beginning of reconstruction. We'll take out all the trash and debris." And so it happened. At the time, the garbage and debris in the entire Orląt cemetery was about four meters high. The whole thing was overgrown with weeds, nettles and large, wild-growing poplar trees. From early morning until late at night, trucks circulated for a month, and almost all of the Energopol workers did community service. And even later, Professor Jerzy Piórecki transported plants to the Cemetery of the Eagles from his wonderful Arboretum near Przemyśl more than once, each time with great troubles and problems. He is now, if I am not mistaken, apart from me, the only Polish participant and witness of those conversations and events who is already alive. A separate chapter of Prof. Jerzy Piórecki's selfless assistance to the Polish communities of Lviv and the Borderlands was written by supporting the open air painting workshops at the Arboretum and the numerous meetings organized by my wife and me with the actors of the People's Polish Theater, activists of Polish Cultural Societies in the 1990s and later. There were many of them. But that's another story.

One Response

It is a very interesting presentation of the entire content and history of Professor Jerzy's extraordinary activities. I had the pleasure of personally observing a lot of activities for 40 years and participating in many of them, mainly in the field of cultural heritage. We are very happy that these tireless activities of Professor Piórecki are passed on to the next generations and that the most knowledge he could pass on to his son Narcyz, currently director. Arboretum in Bolestraszicsch. Best regards. Also on behalf of the Podkarpackie Foundation for the Protection of Monuments.